Seasonality In Financial Assets USD/JPY 1.0

Seasonality is something that some people have a strong belief in and others think it sounds ridiculous, but in what should come to no ones surprise the reality lies somewhere in between. For some things it works relatively well as there are decent cause and effect relationships, and for others it does very little if anything. This post was inspired by a chart crime we saw on Twitter and decided to dig in. As is the case with most heinous chart crimes it turns out there was not much there.

The Case For Seasonality

Seasonality exists in some commodities. It both shows up and makes sense to most people. For instance wheat is planted at the same times each year and harvested at the same times as well. We have four seasons that come at the same times each year. Logically it would make sense that seasonality shows up in a lot of commodities.

But it can also be found in purely financial assets. These relationships do not occur because of planting season or the weather, but instead move due to capital flows and non-economic events. Oh they can also happen just because, or at least for reasons where we don’t have an explanation for.

That last bit is what you need to worry about. A tight relationship with zero reason behind it, is a very weak relationship. On the other hand if you can figure out what is likely happening then maybe you can get some use out of it.

For instance in the stock market the last few days of the month and the first few days of the next month are historically some of the most bullish days of the month and year. Why does this happen? We don’t know for sure, but overtime is seems that people put money to work at the end/beginning of each month.

That explanation makes sense and is a useful tool to help setup trades. In fact we maintain a calendar for the SP500 because of the propensity of the bullish days to work out. We don’t trade it outright, but it is an input.

These type of dynamics show up across financial assets. Some of them are lasting and others appear for a period and then stop working. For instance about 10 years ago someone figured out that 60/40 portfolios had a very big shift at quarter end. They then found that there were a few monster 60/40 funds that rebalanced at this time. For a while you could trade that move, but over time it has been fixed and the edge has mostly vanished.

Other things that can sometimes be seen, or almost seen, on a calendar are central bank actions, month end, quarter end, and year end rebalances, and so many other things that happen on a schedule but are not driven by valuations or other economic based market actions. Worth nothing is that while seasonality has some similarities to cycles it is definitely not the same thing.

One last thing before we start looking at an example is that when looking at correlations a lot of people and some charting platforms statisticians say to use the correlation of percent returns and not on prices. One is far more accurate than others. As you will see we actually look at both, but the percent return correlations are statistically more robust and the price correlations are not.

USD/JPY Seasonality

For this we are looking at the USD/JPY. We use the price only data from 1972 to 11/8/24. Price only means that it does not include any interest that would have been credited or debited to the account anytime a position was held overnight.

In the first chart we are using all of the years. We took all the years, took the daily price returns, and averaged them to get this line. Of course the USD/JPY has not been in a downtrend all of the past 52 years, but on average it has been.

If we look at this year and the year it correlates with the best using the daily returns correlation we actually get 2023. As you can see the two lined up very well for the first half of the year but have started to diverge a LOT since then.

Let’s look at the least correlated year. The 1976 and 2024 series have an inverse correlation for the first half of the year, and since then the relationship has actually improved quite a bit, but over the history of the two data series the relationship has a negative correlation.

If we look at the second best correlation we get 1996. As you can see the two years have mostly moved together aside from the big divergence after their mid year peaks.

If we use the correlations from the price series and NOT the percent return series we get different years. Here we see that 1999 is the year that best matches up with 2024, and the relationship has totally gone off the rails over the past two months.

The absolute worse correlation based on price is 1995. As you can see they both basically move the opposite directions most of the time.

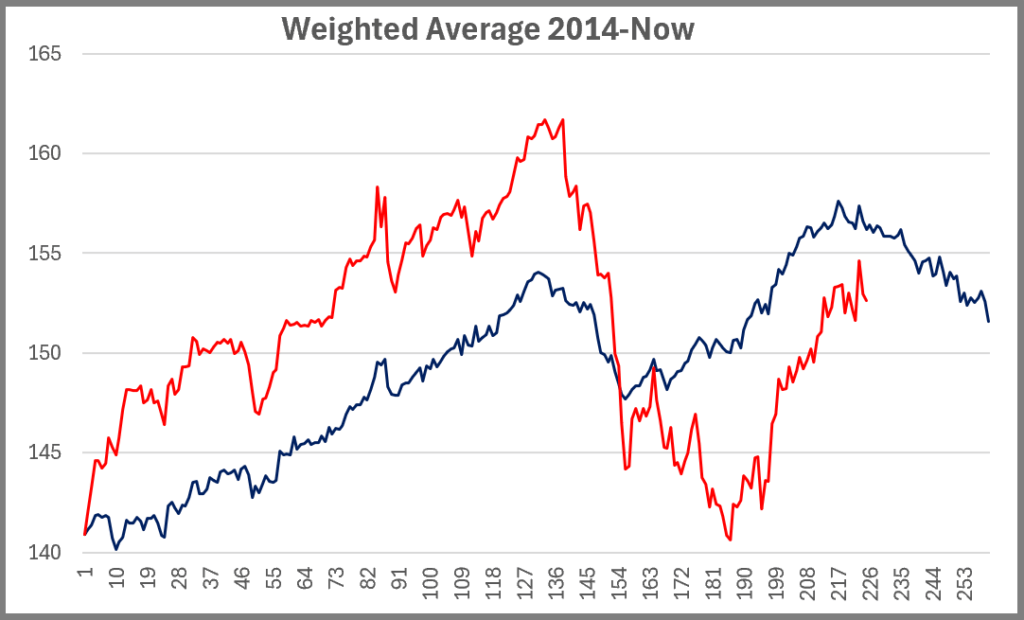

Now lets zoom in and look at the last 10 years. If we look at the normal average of the last 10 years and base them both with the first price of 2024, we get this chart.

Now we take that same data and instead of using a simple average we use a weighted average. Here the more recent years have a higher weight than the older years. In this case you can see a fairly clear relationship as they both rise into the middle of the year, drop, and then started to rise again. Based on this pattern you would be looking for the current move to drop modestly into the last six weeks of the year.

Across all of these charts the only fairly consistent thing we have noticed is that in the middle of the year, around day 120-140, the USD/JPY seems to move lower far more often than not. It is far from perfect and we have not come up with a reason for it, but it is something worth looking into more.

But, and it is a bit but, there is nothing that is even close to a lock. We ran other variations to look for other relationships and came up with pretty much nothing. Sometimes you find something useful, sometimes it is a dead end. In the case of FX this makes maybe more sense than any other asset class as it is purely a financial asset, and not a financial asset that “should” go up or down over time. Equities and fixed income “should” move up over time and commodities have seasons. FX on the other hand doesn’t have a natural directional bias, and as far as we can see has very little visible seasonality.

What About Election Years?

Because we just had an election in the US we also went in and looked at the average of all Presidential election years since 1972. In equities there is a real relationship or cycle here, but in the case of the USD/JPY we see almost nothing. We even went in and played with the axis and still the only thing was about mid year we saw a downturn, but otherwise nothing, and even the downturn was weak.

Next Up

As is often the case we ran into mostly a dead end in terms of the USD/JPY. In the next installment of “Seasonality” we will look at economic expectations using the Citi Economic Surprise Index. We have used a simple model for most of the past 14 years to call the direction of analyst expectations.

Happy Trading,

P.S. If you liked this then take a free two week trial of our service. If you have any questions send me an email or find me over at Twitter @DavidTaggart